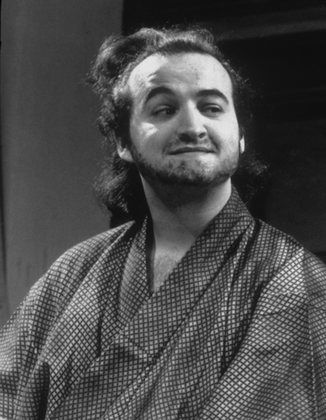

John Belushi was a famous comedian, actor, and musician. He was born on January 24th, 1949, in Chicago, Illinois, and died in Los Angeles on March 5th, 1982. He was a prolific person with a wide variety of roles in his different fields, but he was primarily known as being one of the first cast members of Saturday Night Live, playing one of the Blues Brothers, Jake Blues, in the hit movie Blues Brothers (1980), and for playing a character named John “Bluto” Blutarsky in the college comedy film National Lampoon’s Animal House (1978). [1] On Saturday Night Live, John Belushi had several well-known and liked characters: Saturday Night Live Samurai, Henry Kessinger, Ludwig Van Beethoven, the Greek owner of the Olympia Café, Captain James T. Kirk, Killer Bee, and others. [2]

Although John Belushi did not attend UW-Whitewater for very long, being enrolled in college from 1967 to 1968, he showcased his passion for acting by joining the theatre group and participating in a variety of different plays. One of the plays he partook in was a production of “Night Must Fall,” a psychological thriller first performed in 1935, where he portrayed an inspector in “Night Must Fall.” [1][2] He was also in a play called “The Man Who Came to Dinner” in October 1967,[3] as well as a role in a play called “Winterset” in November 1967.[4] While he was in school, two professors from the drama department worked with him and commented on what Belushi was like as an aspiring actor and comedian. Fred Sederhelm directed Belushi in “Night Must Fall,” a play where the talented freshman was in the role of a Scotland Yard detective investigating and solving the murders of old women in England; he also directed Belushi in “The Man Who Came to Dinner.”[5] In regards to Belushi’s talent, Sederholm remarked that “he was only on stage for 15 minutes, but it was just a riot act.”[6] However, Sederholm observed that Belushi was at his best when he could improvise, and was not as skilled at memorizing and reciting lines. Another drama professor, Fannie Hicklin, noticed this as well, commenting that John Belushi was “undisciplined.” Sederholm also commented that Belushi was “quiet,” and that he “applied himself only to the things which interested him.”[7] The last thing Sederholm mentioned about Belushi was that “Looking back, I can’t say he was going to be a star…A lot of theatre is just plain dumb luck, and he had talent, and he was lucky. He had a lot of guts to stick it out where many people don’t.”[8]

John Belushi was one of the most influential male comedians, showcasing his talent in various ways and creating an immortal mark in comedy that has influenced a plethora of comedians and actors and will continue to influence people in the future.

[1] University of Wisconsin-Whitewater, The Minneiska Yearbook 1968 (Whitewater: University of Wisconsin-Whitewater, 1968), 134. https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.30048828.

[2] “Night Must Fall,” Wikipedia, accessed December 3rd, 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Night_Must_Fall.

[3] “Weird Family Object of Theater Production,” The Royal Purple (Whitewater, WI), October 12, 1967. https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.32935013.

[4] “Winterset Cast Has Rehearsals,” The Royal Purple (Whitewater, WI), November 9, 1967. https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.32935017.

[5] UW-Whitewater Foundation for Alumni and Friends, “Late ‘Animal House’ Star Once Attended UW-Whitewater”, Whitewater Today 19, no.1 (Fall 1987): 5.

[6] UW-Whitewater Foundation for Alumni and Friends, “Late ‘Animal House’ Star Once Attended UW-Whitewater”, Whitewater Today 19, no.1 (Fall 1987): 5.

[7] UW-Whitewater Foundation for Alumni and Friends, “Late ‘Animal House’ Star Once Attended UW-Whitewater”, Whitewater Today 19, no.1 (Fall 1987): 5.

[8] UW-Whitewater Foundation for Alumni and Friends, “Late ‘Animal House’ Star Once Attended UW-Whitewater”, Whitewater Today 19, no.1 (Fall 1987): 5.